|

Wheat N Timing In Spring: Later Is Usually Better

DR. PETER C. SCHARF

COLUMBIA, MO.

Fall 2020 was considerably better for timely wheat planting, emergence, and decent fall growth than the two preceding years. That is one reason why Missouri wheat acres are a good bit higher this year than the last two.

The result is that the crop is in generally good shape coming into the spring.

February is when most farmers who grow wheat start to look at getting on some N. Many farmers who are serious about wheat split their spring N applications, with the first application likely to happen in February.

My research suggests that in most cases, it's better to wait until at least mid-March and apply the N in a single shot. And with a split, it's usually better to make the second application the bigger one.

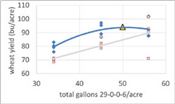

Later N timing worked better in 2020. Gold & black triangle got all N just before jointing. Blue points/line got 17 gal/acre early and the rest just before jointing. Gray points/line got 34 gal/acre early and the rest just before jointing. A single application just before jointing won (max yield and saved a trip). With split N, a low rate at greenup beat a high rate at greenup by 10 bu/acre at rates up to 50 gal/acre.

Here's a case from last year. This was an on-farm strip trial. We only had one small area with zero N at greenup, that's all the farmer was comfortable with. That area made 94 bushels/acre (gold/black triangle in the graph below) after we came back and put 50 gal/acre of 29-0-0-6 on it just before jointing. If we put 17 gallons on at greenup and came back with 33 more, it made the same yield but needed an extra trip (blue symbols and line). Splitting N did not increase yield. When we put 34 gallons on at greenup, yield was 10 bushels behind for any total N rate from 34 to 50 gallons (gray symbols and line), but could catch up by pouring on extra N. 34 gallons at greenup was just not an efficient way to supply N. Overall the fastest and most profitable strategy was just to put on a high rate shortly before the first joint.

Another on-farm strip trial in a different county had similar results, but the greenup N rates were 8.5 or 17 gallons. At the same total N rate, 8.5 gallons early beat 17 gallons early by about 5 bushels/acre across the board. Early N just wasn't used as efficiently and didn't produce as much yield as later N.

In 2019, the situation was reversed-early N was important. The reason was a very wet and cold fall, leading to many fields being planted late, and even those fields that were planted in a timely manner had poor root growth, top growth, and tillering. We chose the best-tillered field of our cooperating farmer, but it was still poorly-tillered relative to most fields in most years. We intended to do a split application with different rates in each split, but the farmer stopped the first application halfway through the field because he was making large ruts. He couldn't get back in the field for three more weeks. At that point, he decided to proceed with a single application in the rest of the field, including a range of rates, but not to apply more N to the half of the field that had received N three weeks earlier.

The result was that the half of the field that received early N made higher yield with less N. Average UAN rate was 16 gallons/acre to produce 91 bu/acre. In the half of the field that was delayed, average UAN rate was 22 gallons/acre to produce 81 bu/acre. This was easily enough yield benefit to have paid for a plane to come in and apply the N in a timely manner.

Tillers are a big deal. You have to have enough, and if you don't have enough in early spring, that is the one situation where an early spring N application is really important and worthwhile.

Counting tillers is a painful process. I've given up on it and prefer to just eyeball the field–if it looks thin at greenup, I want at least some of my N to go down then. If it looks decent or better, I want to wait. If you really want to count tillers, go ahead, but do it right. On your hands and knees, with your fingers pulling the tillers apart from each other so that you don't miss any.

Over quite a few small-plot experiments I've done, the best-rate single-shot rate just before jointing beats the best-rate single-shot rate at greenup by 10 bushels/acre (74 vs 64 bu/ac). That's a lot of bushels and a lot of dollars. Applying the N as a single shot BEFORE greenup is even worse. (If you insist on making a single application in late winter or at greenup, my research shows that ESN, a plastic-coated urea, is your best option for maintaining decent N availability and yield potential.)

BUT if you come into spring with not enough tillers, applying part or all of your N at greenup will usually help to boost the number of tillers that produce a decent head. Don't underestimate the importance of having enough tillers.

In those same experiments, the best split application beat the best single-shot application by only 1 bushel/acre. I don't see where it pays to split in our climate, with our soils.

If you've read this far, you're obviously very interested in N rate and timing for wheat. If you'd like to cooperate on an N rate and timing experiment for wheat this year, give me a call at 573 808 5396. ∆

DR. PETER C. SCHARF: Professor Plant Sciences, University of Missouri

|

|