|

Just How Bad Is The Farm Economy? It Depends…..

SARA WYANT

WASHINGTON, D.C.

As his combine rolls across golden cornfields in eastern Kansas, Ken McCauley is enjoying the view and the numbers climbing up on his yield monitor. Bringing in between 260-270 bushels per acre on some fields with prices firming, he’s looking at a banner year.

Just a couple of hundred miles north and east, Iowa farmer Ray Gaesser thought by mid-August he was going to have the first loss year on his farm since 1984. But some late summer rains boosted yields and his corn will come in at about 218 bushels per acre, with beans averaging 61 bpa.

Farmers just 15 miles away weren’t so lucky with the spotty rains, he reports.

“Their soybean yields are in the 40 bpa and corn ranges from 80-150 bpa. Those yields will not work at all in terms of profitability,” he adds. Of course, those hit by the derecho may not have any yields at all and will count on crop insurance to help fill some of the gaps.

There’s no doubt that farmers, ranchers and growers across the country have seen dramatic economic swings through most of 2020. Between COVID-19 supply chain disruptions, hogs that had to be euthanized, wildfires, hurricanes, derechos, droughts and uncertainty over export markets, there have been a number of reasons for producers to be nervous about their bottom lines as they near the end of the year and look ahead to 2021.

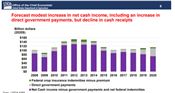

USDA is predicting that net farm income is on the upswing – based in large part on a huge infusion of government payments. Based on its September forecast, USDA expects NFI to increase $19 billion (22.7 percent) to $102.7 billion in 2020, after increasing in both 2018 and 2019. Net cash farm income, which includes cash receipts from farming as well as farm-related income and government payments, is forecast to increase $4.9 billion (4.5 percent) to $115.2 billion in 2020.

Land values are holding strong, interest rates are very low, and debt-to-asset ratios – while increasing – are still near historical lows.

“The debt-to-asset ratio, in aggregate, for the U.S. ag sector is still under 14 percent. It has been trickling up a little bit over the last couple years, but a modest increase. Interest prepayment capacity has actually been improving – despite the fact that debt has been increasing we have seen the effect of those low interest rates and higher net farm income, improving our interest repayment capacity,” USDA Chief Economist Rob Johansson explained during the Kansas City Ag Outlook Forum.

But underlying those numbers are some significant reasons to be concerned about 2021 and beyond.

Still unknown: how COVID-19 will continue to disrupt markets and demand, whether government payments will continue to be robust and whether or not U.S. farmers can pivot to gathering more of their income from the marketplace.

“It bears mentioning how disruptive this coronavirus has been for the U.S. economy, compared to some other shocks to GDP growth in the United States. Just looking at the financial crisis from 2007 compared to the unemployment that we saw with coronavirus, it's quite dramatic,” Johansson added.

He pointed out how much spending power the globe has lost over the past year, with commodity prices reflecting that for most of the year. At the same time, he noted that we are seeing a recovery, even though we don’t know what’s going to happen with the coronavirus in the fall.

“We have seen a tightening situation with respect to cash receipts for farms. On the other hand, we have seen a lot of government payments going out, that has driven net farm income and net cash income, higher over the last couple years,” Johansson said.

John Newton, Chief Economist for the American Farm Bureau Federation, broke down the numbers a bit further when he spoke during the Kansas City event.

“When you deconstruct USDA’s farm income forecast from September, NFI jumped 19 percent to $103 billion, but $37 billion is through federal support payments. The cash receipts – money from the marketplace – actually declined by $12 billion.

“Cash receipts from crop and livestock sales are the lowest they’ve been since 2010. So that creates a pretty challenging farm economy.”

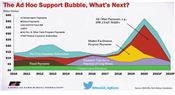

“Seeing 36 percent of our net farm income come from government payments will not be sustainable. We need to figure out how do we get to the other side of this,” Newton emphasized, while asking: “How do we get back to getting our money from the market? How do we see and sustain higher commodity prices? Where is the next ethanol?”

Policy expert Brad Lubben, an extension associate professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, agrees that the broader outlook for 2021 is more complex.

“The recovery in crop prices is rewarding those that lag in their price risk management strategies, but it definitely is helping cash flow this fall and presumably lowering expectations of farm program payments to come next fall (2020 crop payments in October 2021),” noted Lubben. “The higher crop prices together with CFAP, CFAP2, and (Prevent Plant) payments have provided a significant amount of cash flow.

The assistance of the last three years has helped push farm income higher each year since the low of 2017, he added.

“That also means it has pushed off some of the difficult economic decisions that would need to be made in response to lower prices, including production decisions, equipment investment, and land values. Barring further assistance next year, the real cash flow crunch could come in 2021 even if market prices are modestly higher.”

Lubben says livestock producers are also looking at stronger commodity prices and improved trade prospects, “so there is some optimism, although they arguably have had to dig out of deeper holes this year with demand losses (export and high-end restaurant trade) and supply chain disruptions,” Lubben said.

He added that “there is much more concern in livestock circles than in crops as to market performance and the role of risk management. The recent substantial increases in federal subsidy levels for LRP insurance does provide yet another tool to livestock producers but doesn’t guarantee it will solve the challenges."

For both crops and livestock, “the short run may be about managing risk and volatility, but the long run is always about price and costs.

“Producers can look to improved trade prospects due to hoped-for fulfillment of the various agreements implemented in 2020, particularly with Japan and China. That offers some price strength but doesn’t negate the ability of U.S. and other global producers being able to ramp up production,” Lubben emphasized. “Ultimately, producers are faced with the eternal challenge of controlling costs and improving efficiency. That is not a new story, but is still the underlying reality.” ∆

SARA WYANT: Editor of Agri-Pulse, a weekly e-newsletter covering farm and rural policy. To contact her, go to: http://www.agri-pulse.com/

|

|