|

Reflections

Figure 3. A student worker at University of Missouri-Fisher Delta Center in Portageville,

Missouri detassels corn plants in research plot.

DR. GENE STEVENS

PORTAGEVILLE, MO.

This article is the first in a series on my childhood experiences on our family farm in Tennessee and my work at the University of Missouri and Mississippi State University.

In the summer of 1970, I was 13 years old and going into the eighth grade when a major corn disease epidemic occurred in the Southeastern United States. These are my memories of Dad when he realized there was a problem with our corn. My family milked about 140 Holstein cows, raised corn silage for feed, and grew cotton for a cash crop. My dad (Ralph) and uncle (David Carl) were partners in the farming business and family members were the workforce (Figure 1). Mom and Dad had my older brother, Johnny and me. My aunt and uncle had five sons.

Cotton farming and having dairy cows had its good and bad points. Generally, cows came first on the farm. We were often busy planting or cultivating cotton and had to leave a field for milking or tending to a sick cow. But the diversification helped even out the ups and downs of prices. Both dairy and cotton were affected by changing government support programs. There were decades such as the 1980’s with low cotton prices and fair milk prices; and vice versa in other times.

Dairy farming is confining work. Cows are milked twice daily, 365 days a year. Milking started at 4 or 5 A.M., depending on daylight savings time, and the same hour in the afternoon. The positive aspect of having two families working together is that we were able to alternate schedules. Two Sunday afternoons per month my uncle and my cousins milked so my family could be off. The alternate Sundays we milked and they were off. When a month had five Sundays, whichever family worked the last fifth Sunday did not work. On Monday through Saturday everyone worked with a few exceptions. After I got my driver’s license, I learned that my best chance to avoid milking cows on Saturday evening was to have a date!

Our families also took alternating weeks for summer vacations. We were gone 5 to 7 days depending on the weather. Vacations were taken in the late summer usually during hay baling and after most cotton field work was done. Mom and Dad did not make hotel reservations because they did not know when we would be leaving or how long we would be gone. We usually left the morning after a big rain the previous afternoon or night. Mom packed in a hurry and worried that she might forget something. During our trip, Dad would frequently call back home to check in with my uncle. If it was still raining, we might stay longer than a week. The summer of 1968, we left for Hot Springs, Arkansas and ended up in San Antonio, Texas at the World’s Fair.

In 1970, Mom and Dad decided to take Johnny and me deep sea fishing at Destin, Florida. Riding in the car was frustrating. Dad often slowed down or stopped to look at crops along the road. Ironically, my wife complains that I do the same thing as my dad now. The vacation was a bust because a tropical storm in the Gulf of Mexico made the waves too rough for fishing and swimming was dangerous because of wave undertow.

On the way home, Dad became alarmed looking at the cornfields on the sides of the road in Alabama and Mississippi. Being south of Tennessee, he expected corn to mature earlier than at home but not that early. The more we drove the worse the corn looked.

That summer, corn in most of the Southeast United States was damaged by a disease called Southern Corn Leaf Blight. On our farm, the ears only had a few kernels and the stalks were too brown and dry to pack for making good silage. Corn silage was the main feed source for our milk cows. Most years we fed hay just to calves and heifers. Fortunately, each year, Dad and my uncle stored more than enough square bales to feed the heifers. During the winter we took bales from the front of the hay buildings for the heifers but usually fed only about a fourth of the total amount. The following summer we stacked new hay in the empty space at the front of the barn. In the winter of 1970-71, we fed most of the hay that we had. By the time we got near the back of the barns, the hay was dusty and poor quality, but the cows ate it anyway.

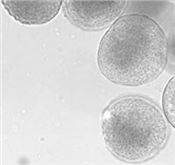

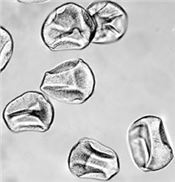

A decade later, I learned the details of the corn disease in a college crop breeding class. It begins with a basic knowledge of the “birds and bees” of hybrid corn seed production. Corn plants make both male (tassel) and female (ear) flowing parts (Figure 2). The kernels on the cobs are the ovules. The parents are “inbreds”, which means they were made by self-pollinating plants for several generations. Tassels are removed to make “female” plants (Figure 3, left). In commercial hybrid seed production, the male parent is planted in rows near the detasseled female parent rows to shed pollen on the ear silks. This fertilizes the female ovules which makes the corn grain. Most effective pollination occurs by mid-morning. By noon, pollen grains have dehydrated (Figure 3, right). When the ears are mature, hybrid seeds are harvested from the female corn rows.

To save time and reduce costs, plant breeders developed male sterile corn inbreds which do not require detasseling. Prior to 1971, most of the corn seed companies used female inbreds with the same male sterility (cms-T cytoplasm maize) trait. Unfortunately, plants with this gene are highly susceptible to Race T of the fungus Cochliobolus heterostrophus which can cause an aggressive form of Southern Corn Leaf Blight in corn plants. After the losses caused by the blight in 1970, seed companies either switched back to manual detasseling or used other ways of making male sterile plants. The dry weather in the 1971 growing season was not conducive for the fungus, and the blight nearly disappeared.

Plant disease epidemics like the Southern Corn Leaf Blight are rare but devastating when they occur. In the quest to develop elite varieties with higher yield potential, plant breeders should also work to maintain diversity in the germplasm of parent lines. Farmers can minimize their risks by planting more than one variety of a crop on their farms and use different seed sources. ∆

DR. GENE STEVENS: Professor- Cropping Systems, Division of Plant Sciences, Fisher Delta Research Center, University of Missouri

Figure 1. David Carl (left) and Ralph (right, my dad) Stevens were partners in our family farm.

Figure 2. Corn plants make two flower parts --female (left) the ear and male (bottom) the tassel.

Magnified viable pollen (left).

Dehydrated pollen (bottom).

|

|