|

Can Muddy Conditions Cause Calf Deaths?

DR. TERESA L. STECKLER

SIMPSON, ILL.

The mud is deep – need I say more?! The mud situation in the Midwest has become the bane of everyone with livestock, not just cattlemen. Traditional winter grounds are, in some cases, belly deep with mud. The lack of freezing temperatures has definitely not helped the situation, especially in southern Illinois. Adding to the mud issue are the oscillating temperatures requiring treating cattle for pneumonia. A tough start to the year!

However, there is a very important issue that I have been hearing about – loss of calves and cows. Calf losses (percent of calves born, if known) from different farms reported to me are: 3 (30 percent), 7 (50 percent), 27, and over 40. There are additional losses, but you get the point. Any loss is devastating but the average percentage of calves born alive but dying before weaning for all herd sizes was 3.6 percent (2010 APHIS report).

So what is different about this year? Basically from what I hear it is the mud. However, the mud has played different roles. Some calves (and cows) died because they became stuck. Others died due to hypothermia; mud can reduce the insulating ability of the hair coat. While others died due to pathogens; mostly by one week of age.

Mud harbors bacteria and other pathogens, especially from manure, that can affect cattle health. Baby calves are particularly vulnerable before they receive colostrum. A mix of mud and manure (also ample rain without freezing temperatures) in a calving lot can lead to dirty udders. When the newborn calf suckles dirty udders, he ingests bacteria along with the colostrum. A race ensues between the antibodies from colostrum and the pathogens. If the antibodies are first then the calf should be fine, provided the colostrum is of high quality. However, if the calf nuzzles a dirty udder or can’t find the teat and nuzzles a dirty flank or brisket before he finds a teat, then the pathogens win and disease will ensue.

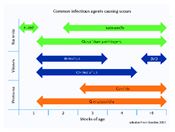

Some of the bacteria that can cause deadly scours in newborns or toxic gut infections in older calves are present in the soil wherever there have been cattle feces – see image for time of calf susceptibility to bacteria, viruses and protozoans. Wet conditions, like we have been experiencing all winter, make it much easier for calves to ingest these pathogens. Dry ground is always a safer environment for calves than mud; they are less apt to pick up scour-causing bacteria or the toxin-forming bacteria that cause acute and often fatal intestinal infections. Some clostridial infections (such as C. perfringens, which cause various types of “enterotoxemia”) and E. coli infections are much more prevalent in muddy conditions than when the ground is dry or frozen. Calves nibbling mud or drinking from mud puddles are always at risk for digestive tract infections.

Calves born on wet, muddy ground are also more vulnerable to navel ill/joint ill. If the umbilical stump contacts contaminated ground or bedding before it dries and seals off then pathogenic bacteria can enter. A calf born in the mud may need antibiotics as well as intensive disinfecting of the navel stump (applying iodine or some other good disinfectant several times) until the stump is completely dry. Infection may localize at the navel, or may enter the bloodstream and cause septicemia. Septicemia is systemic infection in which bacteria get into the bloodstream and travel throughout the body. In cases of septicemia, the bacteria attack various organs and create a potentially fatal infection, or may localize in certain areas such as the joints, to permanently cripple the calf.

Protozoan pathogens are also lurking in mud wherever there have been cattle. Coccidia and cryptosporidia are spread via manure. Coccidiosis and cryptosporidiosis infections in calves are always more common in wet conditions. Whenever cattle are concentrated in small areas with constant contact with manure they are more vulnerable to massive infection with these protozoa. Calves are especially vulnerable because they have not yet developed any immunity or resistance, often nibble dirt or mud, and/or pick up the pathogens when nursing a dirty udder. If cattle must lie on contaminated ground, such as mud mixed with manure, the hair coat becomes dirty also then calves can pick up the pathogens when licking and grooming themselves.

One of the things that can lead to increased incidence of illness in calves is the use of big bale feeders in wet weather – in calving lots or pens/pastures where there are cow/calf pairs. If footing around feeders gets churned to mud, there is more chance of the cows having dirty legs and udders. If conditions are muddy, bale feeders should be moved regularly to cleaner, drier ground. If this is impossible, clean material such as straw should be put around feeders regularly to keep footing clean and dry. Increased incidence of scours has been noted on a number of farms/ ranches after they began using big bale feeders, especially if the cows' udders must be dragged through deep mud when using the feeders.

Since we have had a muddy environment for most of the winter, anything that you can do to minimize mud and dirty conditions in lots and pastures will help decrease problems. If possible move calving cows to clean, dryer ground, fresh pastures, or provide extra bedding to keep the cows cleaner.

Be sure to monitor your calves closely – death can occur suddenly. If a calf is lost consider having necropsy performed to determine the cause of death to possibly prevent any further losses. ∆

DR. TERESA L. STECKLER: Extension Specialist, Animal Systems/Beef, Dixon Springs Agricultural Center, University of Illinois

|

|