|

Considering Fall Herbicide Applications: It’s Not JUST About The Weeds

DR. KEVIN BRADLEY

COLUMBIA, MO.

As harvest season begins to get underway, some calls are coming in and a number of people are starting to ask about fall herbicide applications. There are a number of factors to consider when deciding whether or not a fall herbicide application might fit your corn or soybean production system, and some of the more important of these are discussed below.

#1. Spring Weather Uncertainty

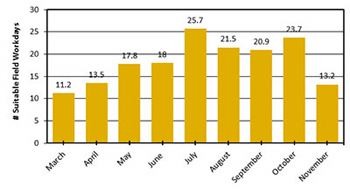

One of the reasons that this whole concept of fall herbicide applications first came about was because of the desire of some producers and retailers to spread out their workloads and remove at least one of the tasks that we would normally do in the spring back to the fall. As illustrated in Figure 1, there are usually less suitable field workdays in Missouri during the months of March and April when early spring preplant herbicide applications are typically made than in the months of October and November when fall herbicide applications could be made. This is largely due to the excessive rainfall that we usually receive in the spring versus the fall, which often makes timely applications of preplant burndown herbicides very challenging during this time of year.

Figure 1. Number of suitable field workdays in Missouri (30-year average).

#2. Impact on Soil Conditions

The removal of winter annual weeds with fall herbicide applications can have a significant impact on the soil conditions experienced at planting. Obviously, dense mats of winter annual weeds can make planting difficult, but the results from our research and from others shows that winter annual weeds can increase soil temperatures, can “wick” significant amounts of moisture from the soil, and can take up available soil nutrients intended for the developing crop.

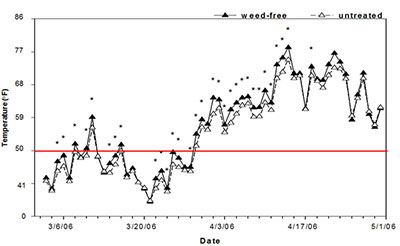

As illustrated in Figure 2, we’ve found that the removal of winter annual weeds with fall herbicide applications resulted in higher soil temperatures when compared to areas with dense infestations of winter annual weeds. In corn, these differences were especially pronounced once soil temperatures reached 50°F (Figure 2). Overall, in our experiments winter annual weed removal achieved through residual fall herbicide applications increased soil temperatures by as much as 5° in corn and by as much as 8° in soybean.

Figure 2. Influence of winter annual weed removal with a residual fall herbicide application on soil temperature prior to corn planting as compared to non-treated plots with a dense cover of winter annual weeds.

The presence of winter annual weeds also leads to reductions in soil moisture content at the time of planting. In our research, soil moisture content at planting was as much as 13 percent higher in corn and 6 percent higher in soybean where winter annual weeds were removed with a fall or early spring preplant herbicide application compared to locations with a dense cover of winter annual weed species.

Lastly, some recent research published by weed scientists at Kansas State University has shown that winter annual weeds are also likely to remove available nitrogen (N) from the soil. When averaged across 14 sites in Kansas, the average N uptake from winter annual weeds was approximately 16 lbs of N per acre. The authors also reported that waiting to remove winter annual weed infestations until spring reduced N uptake in developing corn plants.

#3. Other Pest Interactions

Another significant issue to consider when thinking about fall herbicide applications is that many winter annual weeds can serve as alternate hosts for soybean cyst nematode (SCN). Research has shown that purple deadnettle and henbit are considered strong hosts for SCN while field pennycress has been classified as a moderate host, and shepherd’s-purse, small-flowered bittercress, and common chickweed are weak hosts.

Additionally, one of the most studied insect-weed relationships is that of the black cutworm moth. Fields with henbit and other winter annual weeds that are flowering in the early spring are attractive sites for black cutworm moths to lay their eggs, leaving the larvae to hatch and feed on the developing corn crop.

In our own experiments, we have also seen that winter annual weeds can serve as alternative hosts for corn flea beetle and some other Lepidopteran insects in corn. In soybean, removal of winter annual weeds with fall herbicide applications reduced total insect populations 10-fold soon after soybean planting compared to areas where winter annual weeds remained until 7 days before planting.

#4. Weed Management

Since fall herbicide applications are supposed to be mostly about the weeds, I will finish with three points about the utility of these programs from a weed management perspective only. The first point is that all fall herbicide applications are not created equal. While it may be tempting to cut costs and apply a non-residual herbicide program like glyphosate plus 2,4-D in the fall, it is important to recognize that this kind of approach will only provide control of the winter annual weeds that are present at the time of application. These non-residual herbicide programs don’t offer any control of weeds that may emerge after the initial fall application. And in some years, we can get significant germination of winter annual weeds throughout the winter months, depending on the species and the type of weather conditions we are experiencing. This is why I believe residual herbicide applications are generally a more effective option; they offer control of later-germinating winter annual weed species that might not be present at the time of the initial application.

Second, for the most part the fall residual herbicide programs that are commonly promoted by the different companies provide good control of winter annual weeds. In fact, from just a winter annual weed control perspective, it is often difficult to differentiate these programs from one another. These programs are usually differentiated by their price and by their planting restrictions (for example, whether you can plant corn and soybean or just soybean). So my second point is: these fall herbicide programs all generally provide good control of winter annual weeds but don’t expect control of summer annual weeds as well. There are very few residual herbicides that are applied in the fall that can offer any appreciable level of summer annual weed control, especially in soybeans, and especially in our environment here in Missouri. That may be different in some other states but I believe it is a true statement in Missouri with the winter and spring weather conditions we normally experience. Certain herbicide programs may offer some minor suppression of our earliest emerging summer annual weeds, but minor suppression only, and only for a short period of time.

My third point is basically an extension of point #2, and that is: whether or not a residual fall herbicide application “counts” as an additional herbicide mode of action for a resistant weed depends on the weed species. As discussed above, most fall herbicide programs do not offer any control of summer annual weeds at all, so to count a fall residual herbicide as an additional mode of action on resistant waterhemp, for example, would be a mistake. These products do not provide any control of waterhemp populations that are germinating throughout the summer, so they cannot be included as an effective mode of action on this species, or as part of a program for the management of resistant waterhemp. However, these fall herbicide programs generally do provide excellent control of horseweed (a.k.a. marestail), and so for this weed they should be considered a component of an effective resistant horseweed management program (Figure 3). Some of the more effective fall residual herbicides for the control of horseweed in soybean include the chlorimuron-containing products like Canopy, Canopy EX, Valor XLT, Authority XL, or others. These herbicides should be combined with a base program of either 2,4-D or dicamba (and usually glyphosate) for effective control of seedlings and rosettes that have already emerged at the time of the fall application.

Figure 3. Inconsistent control of herbicide-resistant horseweed populations like this in the spring may be one reason to consider a fall herbicide application.

Overall, it is clear from the results of our experiments that there are many other factors, other than just weed control, that you should consider when deciding whether or not to make a fall herbicide application. To see more detailed results and recommendations about fall herbicides in Missouri, you can view a slideshow here at http://weedscience.missouri.edu/extension/extension.htm.∆

DR. KEVIN BRADLEY: Associate Professor Division of Plant Sciences, University of Missouri

|

|