|

Student Joins 49 Year-Old Study To Unearth Better Weed Control Practices

CARBONDALE, ILL.

Weeds are a continual challenge for food production. They compete with crops for valuable nutrients, space, sunlight and water, and often result in smaller crop yields. Weed control is estimated to cost farmers at least $1.6 billion annually, impacting profit margins and jeopardizing the global food supply.

Multiple weed control techniques are used to manage this problem, but teams of researchers at Southern Illinois University Carbondale are looking at a unique way to address the complex struggle.

Using no-till practices to reduce weeds

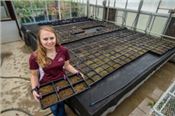

The study starts with soil from a 49-year-old no-till plot at the SIU Belleville Research Center, maintained by farm manager, Ronald Krausz. Sarah Dintelmann, a senior with a double major in crop, soil and environmental management and agribusiness economics, joined the study last year and gathered soil samples from the no-till plot. Working under Karla Gage, assistant professor in the departments of plant, soil and agricultural systems and plant biology, Dintelmann transferred the test soil back to SIU’s Carbondale campus where half was sent for detailed testing and the rest kept in a greenhouse.

This fall, Dintelmann has kept a careful watch on the greenhouse soil to monitor the weed growth and report on the various species that survive in the soil. The careful analysis will reflect how no-till practices affects weed persistence in the seedbank after 49 years.

No-till agriculture is a common agricultural production practice for soil conservation. SIU was a leader in no-till production research beginning in the late 1960’s and throughout the career of weed scientist, George Kapusta, before his retirement in 1998.

Fewer herbicides, better sustainability

Kapusta began this study to look at the long-term interactions of tillage and fertilizer treatments on production, but the weeds have not been studied after all this time. With weeds continually adapting and evolving resistance to herbicides, the team hopes to determine the value of long-term no-till production practices for farmers.

“We have to start figuring out something to do to control weeds besides using herbicides all of the time,” Dintelmann said.

Gage sees the value of looking at alternative ways to suppress weed growth.

“It is important to integrate other methods of weed control with the use of herbicides to help combat the evolution of herbicide resistance,” Gage said. “Cover crops and tillage are examples of cultural practices that growers may choose to use to suppress weeds. However, the use of tillage may also cause a reduction in soil organic matter and other conservation benefits.”

Looking at soil depth to evaluate long-term impact

When gathering the soil samples, the team distinguished between the various depths of the soil to determine if tillage actually placed weeds in the right soil depth to allow access to necessary nutrients and sunlight to encourage unwanted growth. The samples were taken at multiple inch variables, two-, four-, six- and eight-inch depths, to evaluate the growth.

The team is hoping to learn more about the weed distribution in the soil to improve our understanding of tillage as a management practice.

“We wanted to see if tillage actually threw seeds down into the 6-8 inch depths,” Dintelmann said.

If weed seeds are deposited deep in the soil by tillage, they may remain dormant for long periods, even decades, before they eventually lose the ability to germinate and grow. That is why the team is analyzing the effects of this long-term, no-till practice that may have prevented weeds from becoming part of the soil seedbank.

“The best way to keep weeds out of your seedbank is to prevent them from getting there originally,” Dintelmann said.

Study to be completed next year

While the soil comes from a long managed plot, the actual study of the treatment effects on the weeds began more recently. The team examined the in-field growth and development of weeds last year, and then ran the study again this year to replicate their findings.

The team will compare the results from the soil seedbank study with the in-field weed emergence data from the experimental plots, to see how accurately the seedbank represents the weeds emerging in the field and vice-versa. The goal is to publish the unique research in the next year or so.

A Belleville native herself, Dintelmann sees the research as another important factor for farmers and those in the agriculture industry to consider when it comes to weed control topics.

“There are some other research stations that have almost 50 years of no-till trials going on, but this is the first time anyone has really looked at the weed seedbank composition over that time,” Dintelmann said.

After interning with both SIU’s Belleville Research Center and Syngenta, Dintelmann hopes to use this study as a valuable foundation for her future. After graduation, she hopes to work with crop protection and seeds, and then at some point, work towards her MBA degree. ∆

|

|