|

Farm Bill Process Starts Again: What Could Go Wrong?

SARA WYANT

WASHINGTON, D.C.

It doesn’t seem that journalists like me have had much time to “recover” from the “ups and downs” of what finally became the 2014 farm bill.

But here we go again: Both the House and Senate agriculture committees overseeing development of a new farm bill are already hosting hearings. They plan to gather input and start crafting ideas before the current farm bill expires in the fall of 2018.

Veterans of previous farm bills don’t anticipate that this process will be as difficult as the last one, which started in the summer of 2010 and didn’t result in a bill that President Barack Obama signed until February of 2014.

During a recent meeting with new members of the House Agriculture Committee, Rep. Frank Lucas, R-Okla. – who chaired the committee during work on the previous bill – tried to put the 2014 farm bill into perspective compared to previous farm bills.

“They’ve all been so different,” he emphasized. From his perspective, farm bills have evolved over three distinctly different generations, adapting to reflect different parts of U.S. agricultural history and economic conditions.

The very first farm bill, in 1933, was about supply management because we had stockpiles of excess commodities, Lucas told Agri-Pulse. Subsequent farm bills were used to build upon the tools first used at that time. The second generation of farm bills, launched in 1996, was dubbed “Freedom to Farm” as a way to move farmers away from production controls and target prices. That’s when direct or “transition” payments were first launched and Roberts chaired the House Agriculture Committee.

The third generation of farm bills – culminating in the 2014 bill – was focused on getting rid of direct payments, Lucas said.

“When you have to reinvent the wheel, like we did, it’s tough,” Lucas said of the last farm bill experience. “But like 2002 and 2008, when you are refining existing policy, it’s much easier.”

Lucas predicts that the next farm bill will be a refinement process, rather than a reinvention process.

“I just hope that (current House Agriculture Chairman Mike) Conaway doesn’t have to go through what Pat (Roberts) did in 1996 or I did in 2012, 2013 and 2014.”

In order to share the challenges involved with writing a new farm bill, Agri-Pulse launched a new in-depth editorial series: “The seven things you need to know before you write the next farm bill.” It’s designed to help educate those who have never been through the process or might not have seen some of the behind-the-scenes action that our editorial team witnessed.

For example, who would have thought that the farm bill would be defeated and then have to be split in the House, before being sewn back together again with the Senate version?

Or that Senate Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., would have relied on Sen. Pat Roberts’ staff to write farm bill extension language – rather than relying on Sen. Debbie Stabenow, his fellow Democrat and Chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee?

Can we pass another one?

Farmers are already wondering if it’s possible to pass another farm bill, says Mary Kay Thatcher, senior director of congressional relations for the American Farm Bureau Federation.

The answer to that question is “absolutely yes,” she says, but it’s going to require a bipartisan approach. Here’s why.

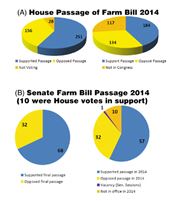

When a farm bill finally passed the House, the vote was 2014 – 251 to 156. As you can see from the pie chart (A), there were 28 who did not vote.

Fast forward to 2017 and the new members in Congress. What if a farm bill came up for a vote this year?

“You would have about 184 of those members that voted for it in 2014 that are still around, about 134 who opposed passage, and a very good chunk, 117 of them, who are brand new,”

Thatcher explained during a recent presentation to the Crop Insurance and Reinsurance Bureau meeting.

“My point: 184 isn’t very far from the 218 House members that you need for passage. So, I think it’s an exceptional chance that as long as we write a good, balanced, robust farm bill, we’re not going to have any trouble passing the next one.”

“I think the very same thing about the Senate, where it was a 68 -32 vote for final passage,” she added.

In chart (B), ten of the votes in the 57 and the 32 were actually House members – who have since come over to the Senate, but they either voted for or against the House bill. Thatcher assumed they’d vote in the same way now that they are in the Senate.

“At 57, we’re only three votes from the 60 percent majority that we actually need. So again, very, very close, I think the support for a farm bill is indeed still very deep,” she added.

Thatcher says that a recent Congressional Budget Office report also provides a good talking point for farm bill supporters: It shows an $81 billion dollar difference in savings since 2014.

“So not only did we save $23 billion dollars when we wrote the last farm bill, but since then, the farm bill has cost $81 billion less than we thought it would,” she explained.

But the “math” could pose challenges

Thatcher says the opposite side of this is, we have $81 billion dollars less to write the next farm bill. And the political dynamics are not a slam dunk.

“The important thing you have to remember is, for virtually every vote in the Senate, it’s not 50 votes you need. It’s 60 votes. Right now we have 52 Republican senators.

“If we want to pass almost anything, and we assume all 52 Republicans will vote as a block, we still need eight democrats to say, ‘I’ll cross the aisle, I’ll be bipartisan.’” That’s generally easier in agriculture than other places, she adds.

But that’s not always the case. For example, trying to overturn the controversial Waters of the U.S. rule, which was often referred to as WOTUS.

“We had several votes on it – The best one that ever occurred for us was in November of 2015, where we had 57 members, but no matter how hard we – corn, wheat, soybeans, cotton, rice, dairy, you name it – worked to try to find three more democratic senators to get to that 60, we could not get three more to go.

“So this is a really good indication of something that seems like we ought to be able to do something about reaching 60 – but three votes short. You need to have that sixty.”

The same type of problem could emerge in the House.

“In the House it’s not the 60 percent, it’s the 218 out of the 435. In many respects, the Tea Party is sort of that unknown,” Thatcher says.

“Less than two years ago, the Freedom Caucus was formed by nine House members who said the rest of the Republican party is simply too liberal and we think you’ve got to be more conservative.” They grew to 41 members. They encouraged members to vote as a block.

“As we look at this new Congress, is this Freedom Caucus going to support Speaker (Paul) Ryan or are they going to continue to be a burr in his saddle like they were for Speaker (John) Boehner, or are they going to try to make President Trump look good. I think it’s too early to really know,” Thatcher adds.

Right now, the Freedom Caucus had 30 members but Thatcher says I that’s largely because it is an invitation only group and new members have yet to be invited. “They will probably be at 35-36 members. But regardless, it’s a pretty good chunk.”

Thatcher says there are 241 Republicans in the House right now. We only need 218, but if that Freedom Caucus of 30+ members votes en bloc and some Democrats vote en bloc vote, all of a sudden (Speaker) Paul Ryan only has 211 votes. If he doesn’t have 218, the farm bill can’t pass. ∆

SARA WYANT: Editor of Agri-Pulse, a weekly e-newsletter covering farm and rural policy. To contact her, go to: http://www.agri-pulse.com/

|

|