|

Ditch The Itch In Your Herd

DR. HEIDI WARD

LITTLE ROCK, ARK.

Winter is upon us, which means lice are getting prepared to snack on your livestock. Lice infestations typically appear in late fall and peak in late winter, when the air turns colder and cattle stand in groups to keep warm. Winter is also when animals grow extra hair, providing a perfect environment for these pesky parasites. Treating the problem of lice requires time and money, but ignoring the problem leads to economic loss.

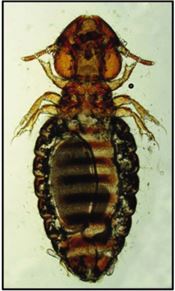

There are two types of lice that affect cattle: biting lice and sucking lice. Lice are tiny insects with claws that attach to hair. The claws are adapted to hairs of a specific diameter, making lice species-specific. In other words, cattle lice will not feed on humans and vice versa because the hair of cattle and humans is dissimilar. Biting lice have a large, blunt head with ventral mouthparts adapted to feed on the skin and skin secretions of cattle (Figure 1). Sucking lice have a narrow head with long, piercing mouthparts adapted to feed on the blood and serum of cattle (Figure 2). Lice irritate cattle causing them to scratch and rub their skin, eventually leading to a decline in health. In addition, lice can carry viruses, bacteria and fungus, which all pose risks for immune-compromised cattle. Animals stressed from growth, pregnancy or underlying disease are most at risk of experiencing secondary health problems from lice.

Lice infestations add to the impact of cold weather, poor winter diet, stress from shipping and underlying disease. Infested animals are often restless and distracted by their discomfort, which keeps them from eating. Cattle can be seen rubbing their face, neck, shoulders and rump to alleviate the itching, which often results in patches of fur loss (Figure 3). The energy that lice steal can have a severe impact on an animal’s immune system and health in general. This impact manifests as anemia, delayed recovery from diseases, poor weight gain or overall unthriftiness.

Lice species of concern in Arkansas are the short-nosed cattle louse (Haematopinus eurysternus), long-nosed cattle louse (Linognathus vituli), little blue louse (Solenopotes capillatus) and cattle-biting louse (Bovicola bovis). The life cycle of lice only lasts 20 to 30 days, with the entire cycle taking place on the host. Females attach their eggs (nits) to hairs, which hatch in 5 to 14 days. When the nymphs emerge, they go through three molts within 7 days. In 14 days, the nymphs become egg-laying adults, thus completing the cycle. Fortunately, the short life cycle makes lice easier to kill with insecticides.

The type of lice infesting the herd is important to know when developing a treatment. Pour-on pyrethroids kill both types of lice, but injectable avermectins mainly kill sucking lice. No matter the product, the label should be followed closely as there might be strict pre-slaughter withdrawal times or environmental precautions. Giving the correct amount is important as these products quickly become toxic to cattle if too much is given. Some products require a second treatment, usually 3 to 4 weeks after the first treatment, to kill lice finishing their life cycle. Adult lice cannot live very long away from the host. Sucking lice die within a few hours when off the host, but biting lice may live for several days as long as they are not exposed to direct sunlight or cold air. Along with treating the animals, the environment (i.e., trees and frequented fence posts) should also be treated prior to allowing new animals into the area. For best results, follow the advice of your veterinarian.

Control and prevention of lice infestation can be achieved by maintaining cattle on a high plane of nutrition. Cattle with an ideal body condition going into winter have better immune systems and can resist the negative impact of lice. Prophylactic treatment with insecticides in late fall will also help prevent infestation, but cattle should be checked regularly during the cold season for recurrence. By having a plan and paying attention to your cattle, you can ditch the itch in your herd. ∆

DR. HEIDI WARD: Assistant Professor and Extension Veterinarian, University of Arkansas

Figure 1. The biting louse, Bovicola bovis.

Figure 2. The sucking louse, Hematopinus eurysternus.

Figure 3. Calf with hair loss from lice infestation.

|

|