Last Effective Bloom Date: How Is It Calculated And What Does It Mean?

DR. TYSON RAPER

JACKSON, TENN.

By definition, the last effective bloom date is the day in which the probability of a new flower developing into a boll and making its way into the basket declines to below 50 percent. Since it is unlikely (probability less than 50 percent) that fruiting positions which develop after this date will contribute to yield, end-of-season insecticide termination and defoliation recommendations for our area are based upon protecting/managing those positions which will be flowering in the next three days for much of West TN (August 12-15th).

As we know all-to-well from the past three years, using a calendar to trigger management decisions can be tricky (it often feels like your odds for success are better at the roulette table). Still, there is sound research and solid logic justifying these last effective bloom dates. Here is how these numbers are derived:

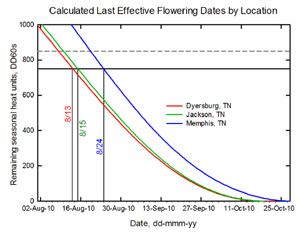

The number of heat units required to mature a flower into a boll has generally been reported to fall between 750-850 DD60s (growing degree days with a base of 60). Using these numbers and location-specific 30 year weather averages from 1980-2010, we can calculate the last day on which a flower will historically have enough heat units to mature. For a visual, please see the graph. Note the reference lines at 750 and 850 DD60s. The colored lines represent the remaining seasonal heat units, graphed by date, for the corresponding locations.

To understand how this works, focus on the Jackson location (green line). After this Saturday (8/15), the green line will fall below the 750 DD60s reference line. Therefore, flowers emerging after 8/15 will likely have less than 750 heat units remaining in the growing season to work with. We MIGHT have the warm September we dream about, but historical data suggests it is unlikely.

Take home: the flowers you see over the next few days will likely be the last to make the basket. Protecting later developing flowers is a financial gamble with less than 1:1 odds. ∆

DR. TYSON RAPER: Cotton & Small Grains Specialist, University of Tennessee