|

With Farm Bill Ink Barely Dry, Crop Insurance Attacks Continue

SARA WYANT

WASHINGTON, D.C.

If you are involved in the crop insurance industry – either as a regulator, provider, or farmer who receives subsidized crop insurance premiums – none of the criticisms in a recent series of reports issued by the Minnesota-based Land Stewardship Project (LSP) will come as any surprise. If anything, the points underscore the reality that debate over the federal crop insurance program did not end with completion of the 2014 farm bill. A wide variety of critics – including many in Congress – are already building the case to make additional changes.

That’s a message not lost on Sen. Pat Roberts who – despite campaign comments about the need to reform the food stamp program – says he’s not interested in opening up the farm bill when he takes the gavel at the Senate Agriculture Committee next year. But still, crop insurance industry advocates are taking a close look at the newest industry criticisms and likely challenges ahead.

Thus far, the Minnesota-based Land Stewardship Project (LSP) has released two of three “white papers” on crop insurance, “Crop Insurance – the Corporate Connection” and “Crop Insurance Ensures the Big Get Bigger” , which echo a lot of the previous criticisms from the Environmental Working Group. A third report, focused on how crop insurance hurts the next generation of farmers get access to the land, is scheduled for release later this month.

LSP leader and Redwood County, MN. Farmer Paul Sobocinski, told Agri-Pulse that he purchases crop insurance on the corn, soybeans and wheat grown on his diversified crop and livestock farm, and can “see the value” of the program. “But it’s important to scrutinize the program more closely and discuss what types of reforms may be needed,” he said, because the needs of “large corporate crop insurance interests could be different than family farm interests.”

LSP noted that crop insurance corporations “consistently generate profits” that are considered far above the “reasonable rate of return” calculated by economic experts. Between 1989 and 2009, crop insurance companies averaged a 17 percent return on equity at a time when the “reasonable” rate was under 13 percent, according to an analysis done for the USDA.

“It’s time we returned crop insurance to its original intent – as a basic, fiscally-sound safety net that supports family farmers and is accountable to the public,” said Sobocinski.

The second LSP report suggests that crop insurance removes so much risk that “people go out and bid up rental rates and land prices” and encourages production on marginal land. LSP suggests the need for an adjusted gross income test so that wealthy individuals don’t receive premium subsidies – an argument made countless times during the farm bill debate.

But some question the time period covered by the LSP reports, which primarily focus on crop insurance before reforms were implemented and before commodity prices headed south. Plus, the reports fail to mention the costs in conjunction with the expansion of the program, covering dozens of new crops and new policies. For example, the farm bill’s addition of the Supplemental Coverage Option could double program costs going forward.

“These types of reports might have been accurate a few years ago, but the past couple of years have not been kind to crop insurers,” says Gary Schnitkey, a University of Illinois agricultural economics professor who specializes in risk management. He also noted that the days of farmers bidding up cash rent are over for now, too.

Three primary changes have occurred in the industry in recent years. As part of the 2008 farm bill, about $6 billion was cut from crop insurance industry reimbursements; in 2010, USDA’s Federal Crop Insurance Corporation renegotiated the Standard Reinsurance Agreement (SRA); and most recently, USDA reduced the premium rates that companies could charge – primarily across the Corn Belt.

“All three of these changes fundamentally changed the risk/reward scenarios for companies compared to the earlier years,” said Keith Collins, former USDA Chief Economist who now consults on behalf of the National Crop Insurance Services. “The story today is dramatically different.”

Indeed, some crop insurance companies decided the current outlook was so bad, they needed an exit strategy. LSP mentioned the John Deere Insurance Company as a firm that “consistently generates profits” in its first report. However, the firm reported losses of almost $5 million in 2010, almost $20 million in 2011, almost $30 million in 2012 and over $35 million in 2013. After 8 years in the crop insurance business, Deere notified shareholders this year that it is exploring options for spinning off that part of its business.

“Anyone looking at returns post -2009 would have shown returns averaging under 5 percent,” said David Graves, President, American Association of Crop Insurers (AACI). “Returns to insurance services below 5 percent are extremely low, if not dangerously low, for maintaining the many contributions of private capital.”

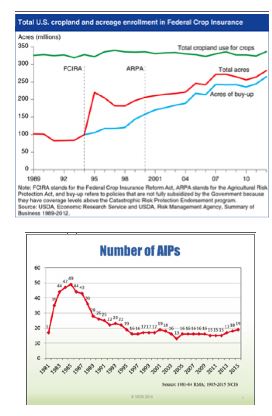

As the NCIS chart shows, the number of approved insurance providers (AIPs) has been in rather dramatic decline since the mid-1980’s. However, four new AIPs entered the crop insurance marketplace since 2011.

Why are new companies entering the market when returns are so low? For Monsanto’s recently acquired Climate Corporation, it was the chance to leverage real-time weather data, along with sophisticated models and precision agricultural knowledge.

Industry insiders speculate that new interest in becoming an AIP might also be driven by some insurance agents, who were frustrated by USDA capping their own compensation in the most recent SRA. Involvement in an AIP might be a way to generate more revenue outside of the cap – even though such a move also involves a great deal more financial, and of course, weather risk. ∆

SARA WYANT: Publisher of Agri-Pulse, a weekly e-newsletter covering farm and rural policy. To contact her, go to: http://www.agri-pulse.com/

|

|