|

Time To Rethink Farmers’ Political Punch?

SARA WYANT

WASHINGTON, D.C.

If farmers’ political influence was measured strictly by the number of farm operators, 1935 would have been a very good year. Peaking at 6.8 million out of a total U.S. population of 127 million, farmers represented slightly more than 5 percent of U.S. citizens.

Certainly, it was a period of time – coming on the heels of the Great Depression – when both the Congress and the White House were focused on addressing the economic plight of farmers suffering from shrinking international markets and dramatic overproduction. Just two years earlier, cotton was trading at 6 cents a pound, wheat at 35 cents a bushel, corn at 15 cents and some farmers were selling hogs at 3 cents a pound.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a New York Democrat, appointed Henry A. Wallace, then a registered Iowa Republican, as his Secretary of Agriculture. Wallace believed that, to have a strong national economy, you had to have a strong agricultural economy and he went to work on crafting New Deal agricultural legislation to tackle problems down on the farm. The result, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, laid the groundwork for many policies that are still foundationally in place today.

In a speech delivered to farmers in 1935, Roosevelt boasted about the important relationship that farmers enjoyed with their city “cousins.”

“If the farm population of the United States suffers and loses its purchasing power, the people in the cities in every part of the country suffer of necessity with it. One of the greatest lessons that the city dwellers have come to understand in these past two years is this: Empty pocketbooks on the farm do not turn factory wheels in the city.”

Both Roosevelt and Wallace talked passionately about the economic interdependence between farmers and consumers, but it also served them well politically. They put together the “New Deal Coalition,” an alliance of voters representing urban Jews, Catholics and blacks, along with farmers and labor unions, in a fashion that powered the Democrat party for decades later.

Fast forward to 2014

The economic, demographic, and political landscapes are all dramatically different in 2014, making it more challenging than ever before for farmers to connect with the consumers who live in cities and the politicians who represent them.

Over time, modern farming practices like hybridization and mechanization made it possible for farmers to escape some of the back-breaking tasks that characterized on-farm production in the 1930s and later years, enabling them to produce more food with less labor. But this trend also accelerated a “disconnect” between those who make a living from the land and those who benefit from their hard work – a gap that appears to have widened in recent years.

“In the old days – if you remember the movie Field of Dreams, it was – “If we build it they will come’ – and that was true in agriculture….. “If we grow it they will buy it.” But those days are not around anymore,” Dan Glickman, a former secretary of agriculture, told Agri-Pulse.

“Now the line is more complex: If you grow it and they want it and they want to know what’s in it, they will buy it. That means you have a consumer that’s more investigative. They want to know what’s in their food,” adds Glickman, who also serves as one of four co-chairs of Agree, a group focused on the transformation of food and agricultural policy systems.

“That means production agriculture has to be more consumer focused. But that’s OK,” Glickman says. “Because the demand is there, too. The innovative producer will meet that demand.”

Still relevant?

Some argue that the growing demand for food on a globe where the population is expected to exceed 9 billion by 2050 (it’s presently at 7.2 billion), puts agriculture in the driver’s seat, regardless of the on-farm numbers.

“When you’re keeping people fed, I’d say you are pretty darn relevant,” emphasized American Farm Bureau Federation President Bob Stallman in a convention speech to his delegates last year.

“While there may be fewer of us in rural America than in other places, we will work harder. We will work longer. We will always stand up for the values that are the bedrock of our nation.”

Yet, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack was one of the first to suggest that the declining number of farmers could translate into declining political clout. Two years ago, while Congress was wrangling over farm legislation, he publicly challenged farmers and ranchers to rethink their rural strategies and try to rebuild the population base in rural America.

“It's time for us to have an adult conversation with folks in rural America. …Why is it that we don’t have a Farm Bill? It isn’t just the differences of policy. It's the fact that rural America, with a shrinking population, is becoming less and less relevant to the politics of this country, and we had better recognize that and we better begin to reverse it,” Vilsack said during a presentation at the Farm Journal Forum in December 2012.

At the time, Vilsack seemed to be underscoring the political polarization that had become painfully obvious within GOP circles.

The GOP majority in the House of Representatives repeatedly struggled to find a path forward on a new farm bill. Their caucus – including a group of about 60 fiscally conservative Tea Party-aligned members who were focused on reducing federal spending above other priorities – seemed unable to reach agreement on how much deficit reduction they could accept in the legislation. On June 20, 2013, the House defeated a comprehensive farm bill in a 234-195 vote, sending shock waves through the traditionally supportive farm community.

Just five years earlier, Democrats who were guided by former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California and former House Agriculture Committee Chairman Collin Peterson of Minnesota had skillfully managed to craft together a new farm bill and also override President George W. Bush’s veto.

Ultimately, the House managed to pass both parts of a “split” farm bill by dividing the nutrition title from the remaining 11 titles and then merging the two versions back together in a conference committee with the Senate.

Clearly, some of the controversy over the farm bill still lingered, as did the questions about future political effectiveness.

“When you have three-quarters of 1 percent of the population involved in food production – if you just look at it from that perspective – the influence of agriculture has really waned,” says former Congressman Cardoza, who now serves as co-chair of the public affairs practice of Foley & Lardner LLP in Washington, D.C. “But it’s also a problem of the industry not advocating forcefully enough and not making their presence known.”

Numbers tell part of the story

The U.S. population has more than doubled since 1935 when Roosevelt was building his “New Deal” coalition, topping over 318 million on July 1. Meanwhile, the U.S. farm population continues to be a shrinking slice of that larger national pie.

The number of principal farm operators dropped about 4 percent from the last U.S. Ag Census in 2007, from 2.2 million to 2.1 million. Farmers now represent less than 1 percent of the U.S. population, based on USDA’s fairly generous definition of a “farmer.”

The American farm population is also growing older, with the average farmer’s age increasing from 57.1 in 2007 to 58.3 in the 2012 Ag Census. That trend is not surprising, but the number of new farmers – a talent pool which could eventually replace those nearing retirement age – does not appear to be keeping pace.

The number of new, beginning farmers shrunk by 23.3 percent since the last Census was released in 2007, however, those grouping of farmers who started farming 10 years ago (between 2003 and 2007) fared slightly better – their numbers only decreased by 19.6 percent.

How does this translate politically?

Regardless of the population, each state gets two votes in the U.S. Senate, which often provides farm and rural interests substantially more political punch per voter than those in urban areas. When you compare a state like Wyoming, with a population on only 582,565 in 2013, to a more populous state like Florida, with a population of about 19.5 million, it’s easy to see how farmers and ranchers can still carry considerable Senate clout in less densely populated states.

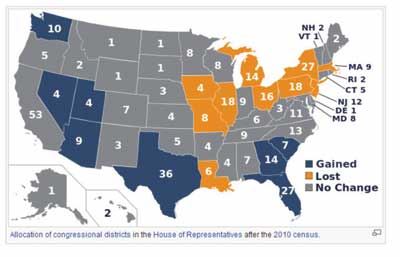

But in the U.S. House, where the number of voting representatives is currently set at 435, these population trends can make a huge difference. Each state is guaranteed at least one congressional seat, but the total number of seats corresponds to the share of the aggregate U.S. population that resides in each state. For now, South Dakota and North Dakota have only one representative each.

In a state where the population has been growing, like Texas, the number of representatives increased from 21 in 1930 to 36 today. The state of Florida, which had 5 representatives in 1930, now has 27.

The map above, indicates how the number of congressional seats in each state changed as a result of the most recent reapportionment in 2012, based on the 2010 Census. Several states in the Upper Plains only have one representative and many others like Iowa, Illinois and Missouri continue to lose representatives. The biggest “gainers” in the pack? Texas, which gained four seats and Florida, which gained two. ∆

Note: This is a condensed version of part one of a six-part series, “Packing Political Punch in Rural America,” which is posted on www.Agri-Pulse.com

SARA WYANT: Editor of Agri-Pulse, a weekly e-newsletter covering farm and rural policy. To contact her, go to: http://www.agri-pulse.com/

|

|