Will Corn Following Corn Face “Issues” In 2011?

URBANA, ILL.

The 2010 season was one

of the most disappointing

in years for corn in many

parts of Illinois, with the

statewide average yield only

157 bushels per acre, just 4.2

bushels higher than the U.S.

average and the third-worst

yield in the past decade. Over

the past 10 years, the Illinois corn yield has averaged

13.7 bushels per acre above the U.S. national

average and has been below the national

average only once (by 4.9 bushels in 2005) and

above it by as much as 25.1 bushels (2008).

The major problem in 2010 was heavy rainfall

in June that resulted in standing water and saturated

soils, which in turn resulted in nitrogen

loss and damage to root systems that could not

be repaired. As a result, affected fields and parts

of fields ended up with shortages of both nitrogen

and water, problems made worse by high

temperatures and early maturity, and in some

cases by dry weather during the latter part of

the grain-filling period.

Corn following corn was particularly hard-hit

in 2010, and there were numerous reports of

larger yield penalties than most have seen for a

number of years for corn following corn compared

to corn following soybean. We saw the

same thing in our research trials, where we

have been comparing continuous corn, corn rotated

with soybean, and corn following either

corn or soybean in a 3-year corn-corn-soybean

rotation. This study was established in 2003,

and so 2008 was the fifth or sixth year of continuous

corn.

While we have found at some sites that the

yield loss in corn following corn or continuous

corn compared to corn following soybean has

generally been less in recent years than the old

10 percent rule of thumb, we have certainly

found little evidence that this yield penalty has

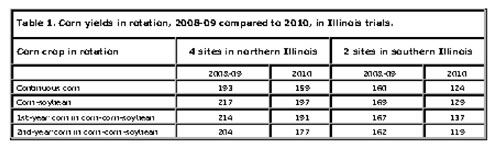

gone away (Table 1). Across four northern Illinois

sites, this penalty for continuous corn was

about 11 percent in 2008-09 and 19 percent in

2010. We did find that second-year corn in the

corn-corn-soybean rotation yielded only 5 percent

less than soybean following corn in 2008-

09 and 10 percent less in 2010, indicating that

having soybeans recently in the rotation does

help to lessen the negative effect of having corn

as the previous crop. At the two southern Illinois

locations, with considerably lower yields,

the penalty for continuous compared to rotated

corn was substantially less, measured either as

bushels or as a percentage.

I provided in an article last fall some of the

reasons that corn following corn did so poorly

in some areas in 2010. In certain ways it was a

“perfect storm” of problems, resulting from lots

of well-preserved residue, cool temperatures for

several weeks after planting, considerable soil

compaction, very little opportunity for spring

tillage, and marginal seedbed conditions, followed

by the large amounts of rain in May and

June.

Does the relatively poor performance of corn

following corn in 2010 mean that we should

worry that 2011 will show similar results? Most

indications are that this shouldn't be our expectation.

Most importantly, field and soil conditions

as we head into 2011 are much different

than they were a year ago. None of the

factors of a year ago – late fall harvest, poor

tillage conditions, lots of fresh residue on the

surface, and much nitrogen yet to apply – exist

this spring. I do not believe I have ever in my 30

seasons in Illinois seen the state as “tilled up”

going into the spring as it is this year. For certain,

if tillage can solve our problems, we can

consider them solved as we head into this season.

One additional benefit is that it has not

been wet for extended periods when soil temperatures

were warm since nitrogen was applied,

meaning that most of the nitrogen we

applied last fall should still be present, with a

good deal of it still in the ammonium form and

so not subject to loss.

Though we can certainly feel good about

preparations we've been able to make for this

spring, we know from history that a good fall

doesn’t always mean a good crop the following

year. While the fact that soils are starting to dry

out nicely in some areas of the state is a good

sign as we head into April, we need to be careful

not to undo the compaction relief provided

by last fall’s tillage by driving on soils before

they’re dry enough. We know that any driving

we do on soils this spring will do some compaction;

soils are typically at or near field capacity

when we’re ready to plant in the spring,

and it’s at field capacity that they are most subject

to compaction. Waiting until soils are dry

enough at depth (not just over the surface) will

help minimize compaction effects, as will using

controlled traffic, making fewer tillage passes,

and lowering tire pressure.

Because we had some 3 million more corn

acres than soybean acres in 2010, and we grow

less than a million acres of crops other than

corn and soybean, we know that some 20 percent

of the corn acres in Illinois in 2011 will follow

corn, providing corn acreage doesn’t drop

from 2010. With high corn prices and a lot of nitrogen

already applied, such a drop seems unlikely.

So should we change anything for corn following

corn this year? No. Our research shows

that both respond similarly to planting date and

to plant population, so those should change

only as soil conditions and productivity might

indicate. We’ve never been able to identify hybrids

that do consistently better in corn following

corn, though corn following corn may tend

to experience stress (primarily drought stress) a

little more often, so that should be factored in.

Diseases related to residues can also be more of

a challenge. And corn following corn typically

needs a little more nitrogen – see the N Rate

Calculator for current numbers.

The important things-having good soil conditions

where the seed is placed and good rooting

conditions underneath the surface-are critically

important for corn no matter what the previous

crop. And the crop needs to be well supplied

with nutrients and protected from pests. Once

we cover these basics, the crop will respond

mostly to weather factors – water and temperature

– that we don’t control. That has always

been true, and will be true again in 2011. Δ

DR. EMERSON NAFZIGER: Professor of Agronomic

Extension, University of Illinois