Energy Prices Are Topsy-Turvy But Irrigation Still Pays The Bills

PORTAGEVILLE, MO.

Increased energy costs

ratchet up farming costs in

many ways: diesel to run

our equipment is higher and

cost is added to fertilizers,

drying, and hauling prices.

However, for the irrigator the

highest fuel bill on his farm is

probably the one for running

those irrigation pumps.

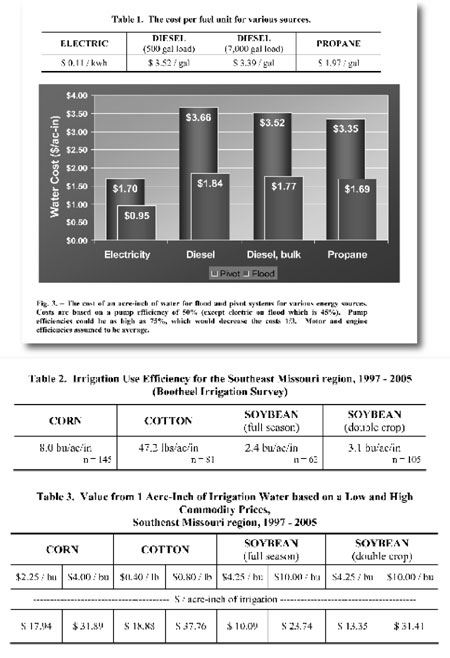

Also, energy costs are frustratingly fickle making

it hard to strategize. Three weeks ago I wrote

an article saying not to choose propane power

units, and instead use diesel if electricity wasn’t

an option. Since then diesel prices have risen

70 cents a gallon, now making propane more

economical then diesel. With higher fuel costs

and volatile prices the first reaction may be to

cut irrigation off. However, doing so would be

like throwing the baby out with the water. Irrigation

is still paying for itself.

One excellent way to examine the bang we are

getting for our irrigation buck is to look at the irrigation

use efficiency (IUE). IUE is the amount

of supplemental yield we get from irrigation divided

by the inches of irrigation water applied.

For example, assume a farmer made 180 bu/ac

inside his pivot, 115 bu/ac in the dry pivot corners,

and had applied 10 inches of irrigation

water. IUE would be (180 bu/ac – 115 bu/ac) /

10 in = 6.5 bu/ac per inch.

IUE is a good analysis tool since it isolates the

investment cost of pumping along with its derived

yield benefit. The cost of pumping an

acre-inch of water depends on (a) fuel source

and (b) method of irrigation. Electricity still remains

the cheapest energy source. The most

recent survey (Mar 12, 2008) of fuel costs in

Southeast Missouri (SEMO) is seen in Table 1.

The cost of water for pivots will be higher then

the cost for flood irrigation due to the added

pressure requirements. Although individual situations

vary, the average cost for an acre-inch

of water for pivot and flood based on the above

fuel costs is seen in Figure 1. Costs range from

a low of $0.95 per ac-in for electricity on flood to

a high of $3.66 for diesel (500 gallon bulk) with

pivots.

The important question now is whether the

added yield we make from each acre-inch offsets

the costs in Figure 1. Data from the annual

Bootheel Irrigation Surveys (BIS) seems to indicate

that it does. First, Table 2 shows IUE data

from these surveys.

Table 3 shows the gross returns stemming

from an acre-inch of irrigation water. Using a

low commodity price (the left hand side on each

commodity column) we see that gross returns

for the four crops range from a low of $10.09 (for

full-season soybeans) to $18.88 (for cotton).

Using the high commodity price, more typical of

current prices, the range is $23.74 (for full-season

soybeans) to $37.76 (for cotton). Clearly,

even when using low commodity prices, all

crops showed profit, even with the most expensive

irrigation water, the pivot on diesel.

Actually, the expected gross returns per acreinch

of irrigation could actually be higher then

shown in Table 3, especially for soybeans. This

is because the dataset used to estimate IUE

goes back to 1997 when irrigated soybean yields

were not like they are today.

Although the above argues for applying irrigation,

almost every year in SEMO there will be

certainly irrigated fields that make no more, or

even less, yield then the dryland portions of that

field. Even the best irrigators find that this occasionally

happens to them. Using BIS data

since 1997 we see that number of instances

when dryland yields were as great or greater

then irrigated yields was 4.0 percent for doublecrop

soybeans, 5.6 percent for corn, 8.2 percent

for full-season soybeans, and 9.3 percent for

cotton. However, even when factoring in these

off years, and even with the current high energy

costs, irrigation remains profitable. Averaging

the commodity values in Table 3 (the higher

ones is used since it is closer to today’s prices)

and using $3.66/acre-inch, which represents

the highest possible water cost, we see that the

returns on pumping costs are about 700 percent.

Δ

Dr. Joe Henggeler is Irrigation Specialist with

the University of Missouri Delta Center at

Portageville.