Alfalfa Weevil Larval Management Options For 2015

DR. WAYNE C. BAILEY

COLUMBIA, MO.

Alfalfa weevil egg hatch is underway in many southern and some central Missouri alfalfa fields. In normal years, alfalfa weevil adults reenter alfalfa fields in late summer after field temperatures begin to cool, laying eggs during fall, winter, and spring seasons when temperatures go above 60oF for a few days or more. Eggs are laid inside plant stems and hatch in the spring depending on when they were laid. Alfalfa weevil eggs develop and eventually hatch after accumulating about 300 degree day heat units based on a 48OF developmental minimum temperature model.

Scouting

Alfalfa weevil larvae grow through 4 larval (worm) stages often referred to as instars, which feed on alfalfa plant tissues as they develop. After emerging from the egg, 1st instars (very tiny in size) move from the hatching sites inside plant stems and crawl to the terminal buds of alfalfa plants. Upon arriving at the terminal buds they burrow into the interior tissues of the green buds and begin feeding with their chewing mouthparts. As the buds expand, early feeding by 1st instars is often seen as small holes in expanding leaf tissues. Carefully opening terminal buds by pinching two sides of an individual bud and carefully pulling the bud in half will generally display the 1st instar if a larva is present. Similar holes in leaf tissue may also be result of feeding by 2nd instars, which due to their expanding size generally leave the interior of the buds to feed on the expanding leaf tissues found on external areas of the terminal buds. The presence of small holes in leaf tissue does provide an early warning that a potential alfalfa weevil larval problem may occur as larvae continue to develop. Numbers of 1st instars are not used in economic threshold calculations, which instead are based mainly on numbers of 2nd, 3rd, and 4th instars. The last two instars feed on all areas of the alfalfa plant, although a majority of larvae will be found in the upper 1/3 to 2/3 of the plant canopy unless numbers of larvae are excessive. As they grow, large larvae consume increasingly greater amounts of plant tissues which often result in economic crop loss through reductions in alfalfa quality and yield.

Although problems with alfalfa weevil have yet to occur this spring, producers in the southern counties of Missouri should scout fields on a weekly schedule beginning now and continue through first harvest. Producers in central and northern counties should begin scouting for alfalfa weevil within the next two weeks. Scouting for 2nd, 3rd, and 4th alfalfa weevil larvae is best accomplished by randomly collecting 50 alfalfa stems (10 stems at 5 different field locations) and tapping them into a white bucket. Larvae will generally be dislodged by this action and allow for an average number of larvae per alfalfa stem to be calculated. Caution should be used when collecting stems as larvae can be easily dislodged from the growing tip of the plant stem by rough handling. It is recommended that the top of the alfalfa stem be cupped in one hand while the plant stem is removed by cutting with a knife near the base of the stem. If an average of one or more larvae per stem is found in the 10 stem sample, then the economic threshold has been reached and control is justified. Infestations often first occur on warmer, south facing slopes of fields.

Management Options

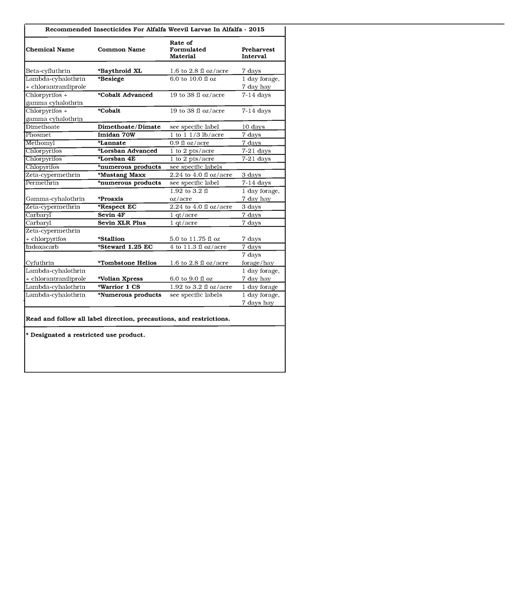

An application of a labeled insecticide is the primary management option used in Missouri for early infestations of alfalfa weevil larvae on alfalfa. Early harvest of the alfalfa by either machine or livestock may be viable options for some producers in Missouri. If early harvest of alfalfa by machine is selected as a control strategy, then the crop is harvested approximately 7-10 days prior to the normal plant growth stage of 1/10 bloom. Data from Missouri studies indicate that alfalfa weevil larval numbers are reduced by about 95 percent with mechanical harvest and about 90 percent by cattle grazing in a management intensive grazing system. Most mechanical harvesters increase the rate of forage drying by crushing the plant stems which results in high mortality of alfalfa weevil larvae at the same time. Mob grazing (high numbers of cattle grazing often for short period of time) of alfalfa removes most alfalfa weevil larvae as they feed on the upper 2/3 of the standing plants. Producers using grazing as a control strategy must be aware of the bloat risk to cattle grazing green alfalfa and risk to the alfalfa stand due to trampling during wet conditions. If an insecticide application is selected, a list of insecticides recommended for alfalfa weevil control follows. Rates are given as amount of product applied per acre. The preharvest (PHI) interval lists the minimum number of days before harvest that an insecticide application can be applied. Some fields, especially in southern Missouri, may require two or more applications of insecticide to achieve acceptable control levels of this pest. Multiple insecticide applications are often due to several peaks in larval numbers resulting from numerous weevil eggs laid throughout fall, winter, and spring seasons.

Other factors that affect efficacy of insecticide applications when used to control alfalfa weevil larval in alfalfa include cool temperatures (below 60 degrees F), which slow the metabolic processes of the developing larvae and often slow the onset of larval mortality to levels below what is normally expected when organophosphate and pyrethroid classes of insecticides are applied at warmer temperatures. Steward insecticide, a recent entry into the alfalfa weevil insecticide market, has demonstrated increased larval mortality when used in cool conditions often experienced in the “Ozark Uplift Areas” of Southwest Missouri. Although Steward’s performance is better than other insecticides under the cool conditions found in Southwest Missouri, efficacies on alfalfa weevil larvae are generally equivalent at more normal conditions. Some other factors include use of low rates of insecticides when larval populations are very high, less than optimal coverage of the infested crop, or possible development of resistance to the pesticide(s) being used. ∆

DR. WAYNE C. BAILEY: Associate Professor of Entomology, University of Missouri