Intensification Has Reduced Carbon Footprint Of U.S. Crop Production

LEXINGTON, KY.

In the scientific community,

it is widely accepted that

the global climate is changing,

and that human activities

are a principal cause of this.

Many human activities produce

“greenhouse gases”.

These transparent gases are

present at trace concentrations

in the Earth’s lower atmosphere. However,

they have the unique quality of trapping

heat there. This trapped heat is driving many

of the recent changes in the Earth’s climate, including

rising global temperatures. See the UK

Extension publication, Agriculture’s Contributions

to Climate Change: Not the “Top Dog”

(http://bit.ly/LrXozR) for more information on

sources of greenhouse gases in the U.S.

Policymakers worldwide are seeking ways to

reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, so that

we can reduce the disruptive impacts of climate

change on water supplies, food production,

human health, and extreme weather. Since carbon

dioxide is the most important greenhouse

gas, policymakers often speak of reducing our

“carbon footprint”.

Agricultural producers sometimes feel blamed

for climate change, especially in the media.

However, U.S. crop producers might be pleasantly

surprised to learn that recent research in

the world’s top science journals tells a different

story.

Recently, four prestigious research

papers emphasized how

crop intensification is an important

way to reduce the carbon footprint

of agriculture. A key point I take

away from these papers is rather

simple: For every acre of land

that we cultivate, we should

grow as much food as is reasonably

possible, with as little carbon

emission as possible.

U.S. producers excel at crop intensification

through agronomic/

horticultural improvement.

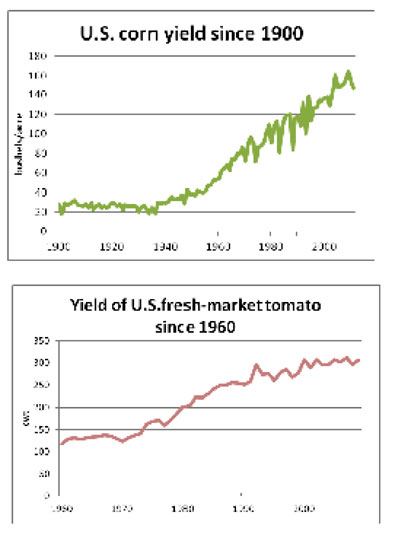

For example, astonishing increases

in grain yields have been achieved

in the U.S., yet yields continue to

rise (Fig. 1). Remarkable yield increases

have been achieved in horticultural

crops, as well (Fig. 2).

Our high-production agriculture

stands in contrast to the situation

in many developing countries,

where crop yields are quite a bit

lower. In such countries, the path

to producing more food often is to

bring more land under cultivation,

which can increase the carbon footprint

of food production by as

much as three times. Pound-forpound

of food produced, U.S. farmers

have significantly reduced the

carbon footprint of food production.

While U.S. agriculture has served

us very well over the years in providing

abundant, safe food, we can

do even more to reduce the carbon

footprint (Extension agents can

help with this). U.S. producers

would probably agree that the ultimate goal is

sustainable intensification: keeping the yield

gains made in intensification while continuing

to improve the sustainability of our agricultural

production systems. But it is also worth recognizing

that the success U.S. producers have

had in intensifying crop production has helped

to reduce climate change.

Bibliography

1. Foley et al, 2011. Solutions for a cultivated

planet. Nature, Volume 478, pages 337-342,

http://bit.ly/MdA5yo.

2. Grassini and Cassman, 2012. High-yield

maize with large net energy yield and small

global warming intensity, Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences, Volume 109.

Pages 1074-1079, http://bit.ly/KhTQCe.

3. Tilman et al, 2011. Global food demand

and the sustainable intensification of agriculture.

Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences, Volume 108, pages 20260-20264,

http://bit.ly/KiNC3L.

4. West et al, 2010. Trading carbon for food:

Global comparison of carbon stocks vs. crop

yields on agricultural land. Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences, Volume 107,

pages 19645–19648, http://bit.ly/KcjEEu.

Reviewed by Dr. Mike Crimmins (University of

Arizona), and Dr. David Van Sanford, Kevin J.

Lyons and Greg Henson (University of Kentucky).

Δ

DR. PAUL VINCELLI: Extension Professor and

Provost’s Distinguished Service Professor, University

of Kentucky